During a series of battles following the infamous Manchurian Incident of 1931 three young Japanese soldiers, heavily armed with explosives, scrambled up to an enemy stronghold with the intention of blasting a hole through the barbed wire fence. They came under heavy fire and detonated their explosives, instantly blowing themselves up. Wether the detonation of their explosives was intentional or not, the three young men accomplished their mission at the cost of their own lives. Japanese military leaders where quick to brand these boys as heroes, willing to sacrifice themselves for the Empire. The legend of the Three Brave Bombers (bakudan san’yūshi) rapidly became a national myth, the three boys posthumous media celebrities and visual representations of their act of selfless bravery heavily circulated throughout the Japanese empire.

The story of the Three Brave Bombers neatly encapsulates several key elements of the Japanese military’s development of wartime rhetoric, coupled with the power of the growing mass media. Self sacrifice, the total submission to the state, the loss of individual identity, and aggressive acts transposed into acts of bravery in the name of defence appear as the pillars of wartime propaganda. Images and stories of the Three Brave Bombers were reproduced time and time again in books, magazines, theatre, paintings and kimonos throughout the 1930s. Perhaps more disturbingly, the incident signalled the government’s readiness to commodify death and to anonymise the individual in order to unite the people in the war effort. The Bombers became accessible, visual symbols encouraging the nation to give themselves to the state in the name of defence and protection, when in reality the Japanese Imperial Army were attempting to expand their empire through acts of ruthless aggression. In order to achieve their aims, the government needed to further secure in its citizens an active identification with nation, ensuring a nationalistic sentiment that exposed then removed those who wished for a more established sense of individual identity.

To answer this call, the Japanese government introduced the National Mobilisation Law in 1937, which called on all its citizens to assist with efforts in the Second Sino-Japanese war. The mobilisation law remained in place as Japan entered conflict with America in 1941, where fear of Western lead modernisation was arguably one of the central driving forces that rallied the people, a fear that had been growing since the end of the nineteenth century. Artists were not exempt from national service, nor were they immune to the fears of foreign modernisation shared by other citizens. A steady stream of Euro-American modernism had been flowing into Japan since the late nineteenth century, and Japanese artist had been quick to adapt to and investigate not only new modes of expression, but also utilise developments in painting technology that were well established in Europe and the US. Yet not all artists embraced the importation of Western artistic ideals, some saw the adoption of foreign practices as un-Japanese. If artists in Japan felt they had been colonised by the ‘overpowering cannon’ of Western art history, as has been suggested by Kinoshita Naoyuki, then anxieties around loss of traditional artistic identity may have surfaced amongst the many artists groups operating at this time. Yet, whilst modernism does not necessarily equal modernisation in the context of the West, the teleological categorisation so favoured by Western art history should be used with caution when approaching art that exists as ‘other’ from the solipsistic establishment of Western art history. Seen through the lens of East Asian art history European modernism could be said to be inseparable from Westernisation.

In addition to the national mobilisation law, government and military leaders began placing even greater emphasis on the physical and mental fitness of their citizens. It was important for the people to be healthy, strong and ready to fight. Ideas of strength and fitness were inseparable from the state-sponsored images of war, the obsession with physical fitness echoing the socialist realism of the Soviet Union during the 1920s and 1930s. The Japanese Government sought total ownership of the body of its people; during a roundtable discussion in 1938 the then Welfare Minister Kido Kōichi declared ‘The body of each single national is not your own, but the property of the state’. It is interesting to note that Koichi would later go on to become the lord keeper of the privy seal, and Emperor Hirohito’s closet confident. Running in tandem with the states desire for healthy people, artists such as Matsumto Shunsuke (b.1912, d.1948), tired of conflict and the continuous anxieties of war, found escapism in depicting strong, healthy bodies inspired by ancient Greece. This demonstrates the subjective duality of health, or how health can be commodified and utilised in the same way to suit opposing means.

Metaphors of health and strength were easily projected onto ideas of painting, providing ground for divisive debate, which was amplified by the arrival in Tokyo in 1938 of the Great German Art Exhibition. The Nazi’s view of modern, expressionistic forms of creation as degenerate art created by developmentally challenged, ‘unhealthy’ people struck a chord with the newly formed Health Ministry, and inspired a deeper interest in Nazi art throughout the Japanese empire. As Maki Kaneko has pointed out, by the late 1930s ‘health' or ‘healthy’ became a common trope to evaluate or describe artworks. In 1938, against this turbulent backdrop of rising tension between the state-sanctioned ‘healthy’, socialist realist inspired Sensōga (war painting) and more subjective, expressionist work of the avant-garde, Katsura Yuki painted ‘Human I’ and ‘Human II’.

‘Human I’ demonstrates Yuki’s anxiety at the increase of nationalism and invasion of every part of life enacted through fascistic government policies and military control of cultural output. In her disturbing image the suggestion of human shapes are reduced to bare minimum; worm-like formations assemble in a line at the bottom of the painting, drifting armless and legless in shallow pictorial space. At the lower right side of the image a taller form rises above the others, seemingly staring out at them, as if from a place of authority. The line of hapless creatures have few features, apart from wide eyes that dart in opposing directions, or stare out at the viewer in a mixture of self pity and confusion.

Two of the central figures wear inane smiles, one grins upside down, its mouth above its eyes. The remaining forms are almost exclusively without lips or mouths. This provokes an unsettling sense of madness, of loss of control, emotion misplaced or teetering on the edge of total breakdown. In the top left corner of the painting another lone ‘blob’ stares mouthless across the picture towards an enormous round head in the top right corner, which has both mouth and eyes. The floating head’s right eye stares back, climbing out of its socket on its own accord, splitting off from its owner and crawling into the picture space as an independent form. The left eye ascends skyward like smoke or a mushroom cloud, and appears to have developed two eyes of its own. Occupying most of the upper half of the canvas rises one of the great symbols of Japanese national identity and power; Mount Fuji. In an act of direct opposition to the visual propaganda intimating the might of the empire, Yuki reduces Mount Fuji to a colourless, flaccid mass barely able to stand on its own.

Given that Mount Fuji is arguably still the most recognisable emblem of Japan and a tangible site for powerful metaphors of resilience and both physical and mental strength, the ability of natural wonders to attract, and eventually transcend use by militarist ideology is clear. Here Katsura’s Fuji is nullified, reclaimed by innocence and dislocated from the grand nationalistic images of the mountain by artists such as Yokoyama Taikan (b.1868, d.1958) whose Nihonga style paintings glorified Mount Fuji in sanitised perfection. For Taikan, Fuji represented the spiritual superiority of the Japanese. Yokoyama was amongst a small number of Nihonga painters supported by the state in the Yōga dominated world of Sensōga. He went on to paint propagandist images of Fuji in the early 1940s that were sold to raise funds for the war effort, the proceeds of which were used to purchase airplanes that were then named after the artist. After the Japanese surrender images of Mount Fuji were heavily censored by the Allied Occupation forces as they considered the mountain to be an imperial symbol.

In contrast to the fearful beings in ‘Human I’, Katsura’s reappropriated mountain is the only glimmer of hope in the darkness of her painting, as it can be read as an immortal object that overcomes the present through its link to the past and the future. Hope crystallised in the natural world is further extended to the presence of a tree suggested by a simple triangle shape supported by a trunk, and a river or pathway that winds its way down the side of the mountain. As we shall see later, the natural world, animals in particular, become important subjects of protest and opposition in Katsura’s art of the postwar period.

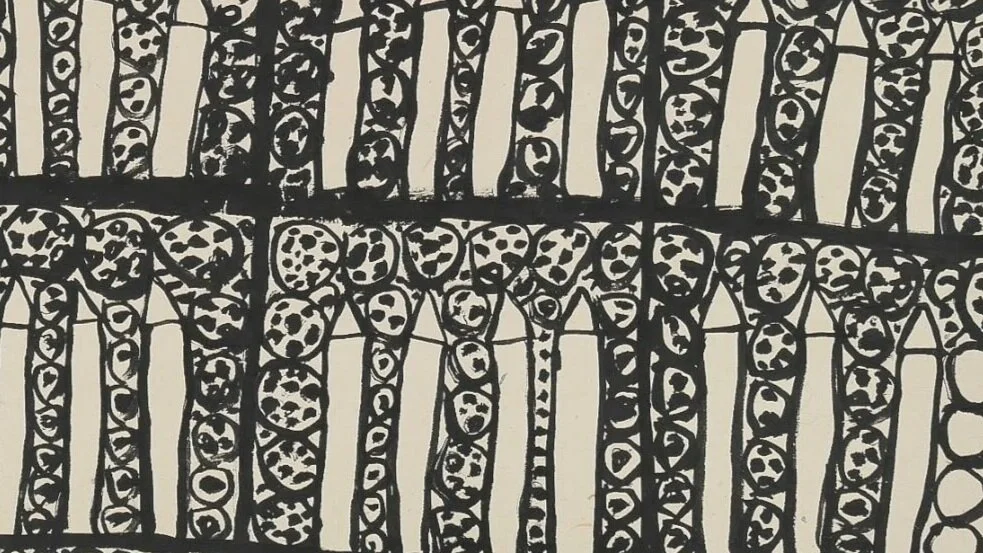

The whole image is tightly cropped from the top and bottom, squashing its inhabitants into the pictorial space. A loose suggestion of perspective is provided by the line of human ‘blobs’ that extends back into the picture plane, and outwards towards the viewer then beyond the edge of the canvas. This also provides a sense of lateral movement across the painting from left to right, suggesting the image extends ‘off stage’ beyond the frame of the canvas. The flattening of and filling of space creates a frenzied immediate painting that is difficult to navigate. Katsura deploys repetition and anthropomorphism not to only obliterate any sense of uniqueness or individuality amongst the human forms, but also to pick apart popular symbols of imperial strength, such as Mount Fuji. A familiar visual language is emerging in Katsura’s work that continues throughout the postwar period, namely direct confrontation of the viewer by mouthless forms, often stacked on top of each other or physically trapped or wrapped in paper or fabric. Furthermore, ‘Human I’ seen through the lens of wartime rhetoric is ‘unhealthy’, lacking any of the obedient, decisive, sacrificial action imaged through the myth of the Three Brave Bombers.

If ‘Human I’ opposes the destruction and invasion of the individual body and the mass call to war, it does so with at least glimmer of hope completely bereft in ‘Human II’. The painting takes the same format as ‘Human I’ and was painted in the same year, yet the sense of potential redemption and escape alluded to through Mount Fuji in ‘Human I’ has been removed. Instead we are left with another tightly packed canvas featuring the seven sorrowful figures from ‘Human I’ huddling in a row. They have sprouted legs, feathers protrude from their heads, and they are now joined by a young child. Encasing them is an oval-like bubble of lighter pigment, the shape of which is repeated again above them in the sky. At the top of the painting hovers a large Zeppelin. It is notable that in 1937, the year before Katsura made ‘Human II,’ the pride of Nazi Germany, the Hindenburg Zeppelin, crashed in New Jersey, USA killing 35 of the 96 people onboard. It is likely that Katsura was aware of the disaster, especially as ties between Germany and Japan had strengthened through the Anti-Comintern pact signed in 1936. Here, the apparition of a Zeppelin hovering over the people is a portent of destruction.

At the base of the painting lies a corpse with a cross over its chest. The figures stand above the corpse, some are looking down at it whilst other look up at the Zeppelin in the sky. It is significant that Katsura chooses to depict her ‘blob-like’ figures as mouthless, yet her corpse is open mouthed and looking down towards the earth. Perhaps Yuki is suggesting the huge numbers of dead speak of the realities of an aggressive drawn out war, or that only in death are the voices of the people freed, if only symbolically. Additionally, this may revisit the idea of the redemptive power of nature seen in ‘Human I’, as eventually all living beings are returned to the earth and become part of the land.

As Namiko Kunimoto has pointed out, ‘Human I' and 'Human II ‘enact dissent’ by altering the aesthetic ‘mode of recognisable nationalist icon’ usually demonstrated through sensōga. To extend this further, I propose that Katsura depicts a deep rooted sense of anxiety over the loss of individuality at the hands of powerful military rhetoric commodified through media and imaged through such stories as the Three Brave Bombers. She also alludes to an ambiguous, psychological avant-garde that resists the blunted certainty of state-sponsored realism. Katsura questions the cultural hegemony enacted by the states channeling of a nationalistic national identity to which citizens were levered into adopting. This conception of personal and national identity was contingent on the state, and was in part predicated on the survival of militarism. As we shall see, this is to collapse in the aftermath of the end of the war in 1945.

Katsura’s distorted, deformed bodies shown in 'Human I’ and ‘Human II’ represent fallible human sites besieged by the state; her images combine a mix of victimisation, blind faith in the empire, and obedience to militarist rule. The critical power in Humans I and Humans II resides in the paintings’ ability to protest state ownership of the human body by showing this ownership taking place, the act of imaging is an act of dissent. Her mouthless forms are far enough removed from resembling people that they avoid the limitations of literal description, reaching out instead for an emotive response from the viewer. The title of the works nullify any remaining ambiguity and reinforces the fallibility of the human being, Katsura seems to reaffirm the universal knowledge that we are all flesh and blood.

Katsura’s act of depicting anxiety at the idea of death in the name of the nation, an idea which many saw as honourable and indeed necessary, was risky business. The nationalistic propaganda of the prewar period pushed the idea of the Japanese as a pure race, free from contamination or influence from outsiders. Any doubts about the strength or willingness of the Japanese people to die for the ‘holy war’ could not be imaged, or even the enter public consciousness. ‘Human I’ and ‘Human II’ oppose this ideology by placing all humans in the same bracket, in the same victim space, at the mercy of one another.

The inhabitants of Katsura’s ‘victim space’ often appear trapped under piles of painterly detritus or metamorphosing into various creatures. The half-human forms appear possessed, wide eyed and unable to function under their own will, they seem at the mercy of forces beyond their control. State control and consumption of the Japanese body, specifically the female body, was to reach new heights in 1941 with the introduction of the national Eugenics law. Government health agencies established eugenics information centres in shopping districts, offering advice on how to identify hereditary diseases, and how to go about sterilisation in a bid to ensure the future purity of the Japanese race. The eugenics counselling centres also provided the government with an opportunity to monitor the population level and gather further information on its citizens. The female body was seen as a product to be used and manipulated; female citizenship was defined by procreation and consumption. Huge numbers of lives had been consumed by the war, which law makers soon realised would lead to a major population shortage, which subsequently led to restrictions on any form of birth control to healthy women of childbearing age.

Full essay available on request